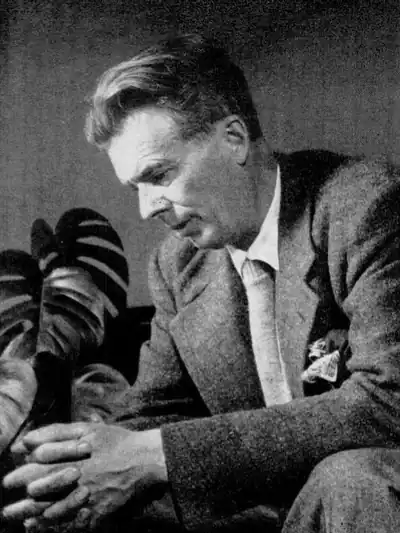

Who Is Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley (1894–1963) was an English writer and intellectual whose career spanned novels, essays, screenplays, and philosophical investigations into human consciousness. He's best known to general audiences for Brave New World (1932), his dystopian novel about a society engineered for comfort at the cost of freedom and depth. But within the world of consciousness studies, spirituality, and psychedelic research, Huxley's later work is what matters most—particularly The Doors of Perception (1954), his account of a mescaline experience that became one of the most influential texts in the modern history of altered states.

Huxley came to psychedelics not as a thrill-seeker but as a deeply read intellectual who had spent years studying comparative mysticism, Vedanta philosophy, and the perennial philosophy tradition. He saw mescaline (and later LSD) as a tool for investigating questions he'd been asking for decades: Why do humans have such limited access to the full range of consciousness? What would it mean to open the "reducing valve" of the brain and perceive reality more directly? His fusion of literary elegance, philosophical seriousness, and personal experimentation gave psychedelic experience a kind of intellectual legitimacy it had never had in the West, and his influence extends through Stanislav Grof, Huston Smith, and the entire modern psychedelic research renaissance.

Core Concepts

- The "reducing valve" theory of consciousness: Drawing on the philosopher C.D. Broad (and ultimately on Henri Bergson), Huxley proposed that the brain functions not primarily as a producer of consciousness but as a filter—a "reducing valve" that limits the overwhelming totality of reality to the narrow band useful for biological survival. Psychedelics, meditation, and certain pathological states temporarily open the valve, allowing a wider range of experience to flood in. This framework—brain-as-filter rather than brain-as-generator—remains one of the most debated and generative ideas in consciousness studies, and it provides a non-pathologizing frame for many experiences that psychiatry tends to label as disorder.

- The perennial philosophy: Huxley popularized this term (borrowed from Leibniz) in his 1945 anthology of the same name. The core claim: beneath the surface differences of the world's great spiritual traditions lies a shared metaphysical vision—that there is a divine ground of being, that humans can directly experience it, and that this experience transforms them. Whether this is literally true is debatable, but as a working framework it has proven immensely useful for people trying to make sense of spiritual experiences that don't fit neatly into a single tradition.

- Psychedelics as a tool for genuine insight, not just hallucination: Huxley's great contribution was to treat his mescaline experience as epistemologically serious—not just as a drug trip, but as a way of seeing that revealed something about the nature of perception and reality. He described seeing ordinary objects (a vase of flowers, the folds of his trousers) with a clarity and depth that felt more real than everyday perception, not less. This framing—that altered states can be more perceptive, not just more distorted—is foundational for the modern psychedelic therapy movement.

- Visionary experience and art: Huxley connected the psychedelic experience to the history of visionary art and religious iconography, arguing that painters like Vermeer and the creators of Buddhist mandalas may have been depicting states of heightened perception that are available to all humans. This link between aesthetics, perception, and spiritual experience added cultural depth to what could otherwise be dismissed as mere pharmacology.

- The human potential and "non-verbal humanities": In his later years, Huxley became deeply interested in what he called the "human potentialities" movement—the idea that most humans operate far below their cognitive, emotional, and spiritual capacity. He was an early supporter of Esalen Institute and advocated for education that developed the whole person: body, emotions, perception, and contemplative awareness, not just the intellect. This vision directly influenced humanistic and transpersonal psychology.

Essential Writings

- The Doors of Perception (1954): A short, luminous account of Huxley's first mescaline experience, supervised by the researcher Humphry Osmond. It's as much a philosophical essay as a trip report, weaving the experience into a theory of perception, art, and consciousness. Best use: still the single best introduction to the intellectual case for taking psychedelic experience seriously.

- The Perennial Philosophy (1945): An anthology of mystical writings from many traditions, with Huxley's commentary. It's an attempt to demonstrate that the world's great contemplative traditions are all pointing at the same underlying reality. Best use: a curated, cross-traditional reading list for anyone exploring spiritual experience beyond the confines of a single religion.

- Brave New World (1932): Huxley's most famous novel imagines a society that has eliminated suffering through genetic engineering, conditioning, and a pleasure drug called soma—but at the cost of freedom, depth, and authentic human experience. Best use: a prophetic warning about what happens when a culture prioritizes comfort over meaning—still disturbingly relevant.

- Island (1962): Huxley's final novel and his utopian counterpoint to Brave New World. It imagines a society that integrates contemplative practice, psychedelic-assisted education, and ecological wisdom into everyday life. Best use: Huxley's most complete vision of what a psychologically and spiritually mature civilization might look like.

- Heaven and Hell (1956): A companion essay to The Doors of Perception that extends the discussion into visionary art, antipodal regions of the mind, and the geography of the afterlife as imagined across cultures. Best use: a deeper dive for readers who found Doors compelling and want to follow the implications further.