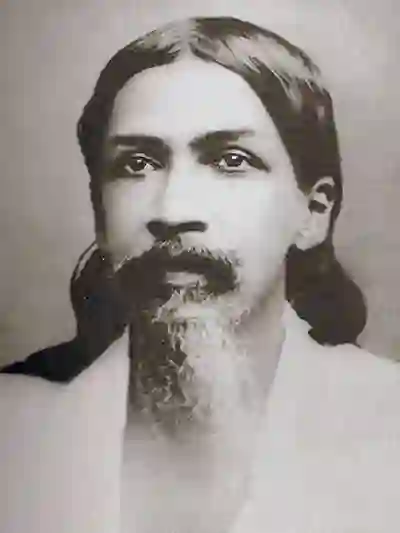

Who Is Sri Aurobindo

Sri Aurobindo (1872–1950), born Aurobindo Ghose in Calcutta, was an Indian philosopher, yogi, poet, and political revolutionary whose work represents one of the most ambitious syntheses of Eastern spiritual practice and Western evolutionary thought ever attempted. Educated at King’s College, Cambridge, where he excelled in classics and literature, he returned to India and became a leading figure in the independence movement, editing the revolutionary journal Bande Mataram and advocating complete self-rule. Imprisoned by the British in 1908 on charges of sedition, he underwent a series of profound spiritual experiences in Alipore jail that reoriented his life from political activism to spiritual work. After his release, he withdrew to Pondicherry in French India, where he spent the remaining four decades of his life developing the philosophy and practice of Integral Yoga, collaborating closely with Mirra Alfassa ("The Mother"), and producing a vast body of philosophical, poetic, and spiritual writing.

Aurobindo matters for IMHU’s mission because he refuses the split between transcendence and transformation that runs through most spiritual traditions. Where classical Indian philosophy often treats the material world as illusion (maya) to be transcended, and Western materialism treats consciousness as an epiphenomenon of matter, Aurobindo proposes a third position: consciousness is the fundamental reality, matter is consciousness in its most concentrated form, and evolution is the process by which consciousness progressively reveals itself through increasingly complex material forms. The human being, in this view, is not the endpoint of evolution but a "transitional being"—and the next stage is not biological but spiritual. His influence on Ken Wilber’s integral theory, transpersonal psychology, and the broader framework of developmental consciousness studies has been substantial, though his original system is considerably more detailed and demanding than most of its derivatives.

Core Concepts

- Involution and evolution as complementary processes

- Aurobindo’s foundational insight is that evolution is not a random mechanical process but the progressive self-revelation of consciousness that has first involved (descended, hidden) itself in matter. The Absolute (Brahman or Sat-Chit-Ananda—Existence-Consciousness-Bliss) first involves itself into increasingly dense forms, culminating in the apparent unconsciousness of matter. Evolution is then the reverse process: consciousness gradually emerging from matter, through life, through mind, and eventually toward higher states he calls Overmind and Supermind. This means matter is not opposed to spirit but is spirit in its most concentrated disguise. (Wikipedia: Integral Yoga)

- The Supermind as the next evolutionary stage

- Beyond the current human mind, Aurobindo maps several ascending planes of consciousness: Higher Mind, Illumined Mind, Intuitive Mind, Overmind, and finally Supermind (or Truth-Consciousness). The Supermind is not merely a better version of thinking; it’s a qualitatively different mode of consciousness that perceives wholes and particulars simultaneously, transcends the subject-object split, and integrates knowledge and power without the fragmentations that characterize mental awareness. Aurobindo saw the descent of Supramental consciousness into earthly life as the next great evolutionary leap—comparable to the emergence of life from matter or mind from life.

- Integral Yoga as "rapid and concentrated conscious evolution"

- Unlike traditional yoga paths that focus on liberation from the world (moksha), Integral Yoga aims at the transformation of the whole being—body, vital energy, mind, and spirit—so that it becomes a fit instrument for divine consciousness to operate in earthly life. The practice uses a "triple labor" of aspiration (opening upward), rejection (discerning and refusing what obstructs transformation), and surrender (progressively offering one’s entire being to the divine). This leads to a "triple transformation": psychic (the soul comes forward to guide the outer personality), spiritual (the consciousness opens to higher planes), and supramental (the entire nature is restructured by Truth-Consciousness).

- The psychic being as the evolving soul

- Aurobindo distinguishes between the surface personality (constructed from mental, vital, and physical experience) and the psychic being—the evolving divine spark that persists through lifetimes and represents one’s deepest authenticity. The psychic being starts hidden and gradually emerges through spiritual development, eventually taking the lead in guiding the outer nature. Connecting with this inner center is the decisive turning point in Integral Yoga, because the psychic being naturally orients the rest of the personality toward truth and transformation.

- All life is yoga

- Aurobindo’s most practically radical teaching is that spiritual practice should not be confined to meditation, retreat, or monastic withdrawal. Work, relationships, creative expression, and engagement with the world are all fields for yogic practice—because the goal is not to escape earthly existence but to divinize it. This "life-affirming" spirituality distinguishes Integral Yoga from most ascetic traditions and makes it directly relevant to people seeking to integrate deep spiritual practice with active, engaged lives.

- My take: Aurobindo is one of the most intellectually demanding spiritual thinkers in any tradition—his system is vast, detailed, and sometimes impenetrably dense. But his core insight is simple and powerful: you don’t have to choose between transformation and transcendence, between the world and the spirit. The whole point is their integration.

Essential Writings

- The Life Divine

- Aurobindo’s philosophical masterwork: a comprehensive exploration of the evolution of consciousness, the nature of Brahman, the meaning of material existence, and the possibility of supramental transformation. It’s long, dense, and sometimes repetitive—but the vision is breathtaking in scope. Originally serialized in the journal Arya (1914–1919) and later revised.

- Best use: the essential text for anyone who wants to engage seriously with Aurobindo’s philosophy. Not light reading—take it slowly, chapter by chapter.

- The Synthesis of Yoga

- Aurobindo’s practical guide to Integral Yoga, integrating the classical paths of Jnana, Bhakti, Karma, and Raja Yoga into a unified approach while adding his distinctive emphasis on the supramental transformation. More accessible than The Life Divine and more directly useful for practitioners.

- Best use: for practitioners who want to understand Integral Yoga as a living discipline rather than a philosophical system.

- Savitri: A Legend and a Symbol

- Aurobindo’s spiritual epic poem—nearly 24,000 lines exploring the soul’s journey through evolution, the confrontation with death, and the triumph of divine consciousness. Many consider it his greatest achievement. It’s not easy reading, but at its best it’s some of the most luminous spiritual poetry in the English language.

- Best use: for readers who respond to poetic and mythic expression—read it as contemplative literature, a few pages at a time.

- Essays on the Gita

- Aurobindo’s reinterpretation of the Bhagavad Gita through the lens of Integral Yoga. Arguably the most accessible of his major works and an excellent introduction to his thought for readers already familiar with Indian philosophy.

- Best use: the best entry point for readers coming from a background in Hindu philosophy who want to see how Aurobindo reframes classical teachings.